Formalizing Lesswrong-Style Science

Published:

Being Clear About What We’re Talking About

I’ve been reading some of Yudkowsky’s Sequences recently and I’ve got to say, even though I think Eliezer’s conduct on twitter and views on safety are fairly extreme, I really like the way he thinks about probability, information, and causality. He clearly has an intuition built from thinking deeply about the implications of basic ideas, and I can respect that. I read somewhere that people complain that he doesn’t bring any new ideas to the table. I disagree. I think in the graph of ideas, he hasn’t found new nodes, but he has a unique and interesting set of edges that map a bit better to human intuition than normal.

The thing that annoys me about the LessWrong brand of rationalism and probability theory is that it often isn’t careful about the specifics of what it’s talking about, and so it’s impossible to develop new intuition or even bake the intuition that exists into pre-existing mathematical machinery. It feels sort of like he’s telling a tribesman in new guinea that a computer is sort of like a vision that lives on the water, and the vision tells you things if you act in certain ways or press on the water, and that’s how he knows what the weather will be tomorrow. The tribesman doesn’t know what a computer is after this and certainly couldn’t build one, even if this conversation gave him some fuzzy intuition.

I have a hardline opinion that the importance of baking new concepts into pre-existing mental machinery is the most underemphasized thing in all of education, and that if schools were built around adding to existing knowledge rather than creating temporary isolated subgraphs that disappear after exams, we’d be a lot better off as a society. My specific experience has been that if I don’t add edges to what I already know, I lose a new node of knowledge almost immediately; however, if I bake it in, it permanently adds to my map of the world.

The specific set of examples I’m thinking about with this lesswrong stuff is all the times Eliezer talks about probabilities and the scientific method in terms of possible-future-worlds without connecting it to any formalization. So let’s get clear about what the fuck we’re talking about and build a proper formalization that maps on to existing machinery.

Defining Universes

First, we need to define what we mean by “possible future worlds”. Probability uses sets under-the-hood to define “things that happen”, and includes a probability measure $P$ that maps sets to scalar values between 0 and 1. So, let’s map out a universe. Set an origin point (I prefer the location right in front of my nose). Call that origin point $\mathbf{0}$. Now define a cartesian coordinate system in 3D spreading out from that origin point. It extends across the entire known universe. Units are totally arbitrary, so let’s say that a meter is one unit. Now the location of every point in the universe is associated with a 3-vector $\mathbf{p}$.

We can define shapes in 3d with planes of boundary points. There can be objects at these planes. Let’s build a simple abstraction: every point is associated with some density (characterizing how many mass-units are in its local volume). We can think of every* such point as indices into a tensor, with the scalar value at the index being the local density. If we do this, the universe becomes a big tensor $\mathbf{U} \in \mathbb{R}^{p \times p \times p}$.

$\mathbf{U}$ defines the state of the universe at a particular point in time. But we don’t just want frozen points, so let’s add a time dimension, so that we can move along it and watch the universe change. We get $\mathbf{U} \in \mathbb{R}^{t \times p \times p \times p}$.

(*One problem with this growing formalization is that we’re forced to discretize, meaning, if we zoom in enough we lose continuity. The fix for this is saying that $\mathbf{U}$ is a function: you give me four real numbers, and I give you the local density at that point in spacetime. But let’s think with tensors for now since that’s easier to work with, and all the intuitions are the same).

There are problems with this formalization. For instance, there are different types of densities: One $kg/m^3$ of hydrogen is different than a $kg/m^3$ of Oganesson-118 (an incredibly unstable superheavy element). But we’ve reached an important point: we have the exact amount of formalism that we need to move on into probabilities, and we can just figure that there’s some close-to-isomorphism that puts the rest of the details of the actual universe into the same-ish mapping. (I am comfortable being handwavy here because we already have sufficient detail to get into probabilities)

Probabilities of Possible Universes

An outcome in the formalization we’re building is exactly one state of the world at a particular time: $\mathbf{U} \in \mathbb{R}^{t \times p \times p \times p}$. But in probability theory, probabilities are functions defined on sets of outcomes called “events”.

What do we want events to be? Well, we are considering different possible universes, and we want to be able to get at probabilities of possible futures, or of possible alternative realities that fit some guess or another. This is just a bunch of $\mathbf{U}$s. So an event is some collection of universes $E = {\mathbf{U} \in \mathcal{U}}$. We call a particular $E$ an event, and $E \subseteq \mathcal{U}$. Here, $\mathcal{U}$ is the set of all possible universes: it’s every 4-tensor that exists. There is some subset of $\mathcal{U}$, linear over $t$, that defines the spacetime trajectory of our actual universe (we can call this $\mathcal{R}$ if we need it, for ‘real universe’). We often want to condition on all ${\mathcal{R}: t \geq t_0}$, where $t_0$ is the present time, to think about future events (however, we don’t ever have perfect information, so we always must approximate that conditioning). The set of possible universes that we might actually care about is some low-entropy manifold on $\mathcal{U}$, because if you just pick a random outcome/universe $\mathbf{U_i}$ it will almost certainly have roughly uniform density across the whole tensor, like noise.

Now we can start to get specific, and we can start bringing in the machinery of probability, because we know what we mean by ‘outcome’ and ‘events’. The set of all possible events is called the event space $\mathcal{E}$. The probability measure $P$ simply maps events to probabilities, $P: \mathcal{E} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{[0,1]}$, such that $P(E) = p$. Each outcome isn’t associated with a probability, but with a local probability-density. We integrate over outcomes (“possible universes”) to create probabilities. (consider that we are integrating rather than summing - because each element of our 4-tensor exists on the real number line, the set of universes exists on a continuous space).

$\mathcal{U} \in \mathcal{E} $ is also called the sample space, and it has probability 1. Every other event is a subset of $\mathcal{U}$. If we divide our sample space into disjoint events (remember, “groups of universes”), $E_1, \cdots, E_n \subseteq \mathcal{U}$, then $\sum_i P(E_i) = 1$.

We often want to define events based on some condition about the world. The condition can be anything. “the set of universes in which my hypothesis about the world is true” is a useful family of conditions. “The set of universes in which I guess that I hung up my keys by the door, and then my keys are actually by the door” is a member of that family, and defines one event.

The Scientific Method

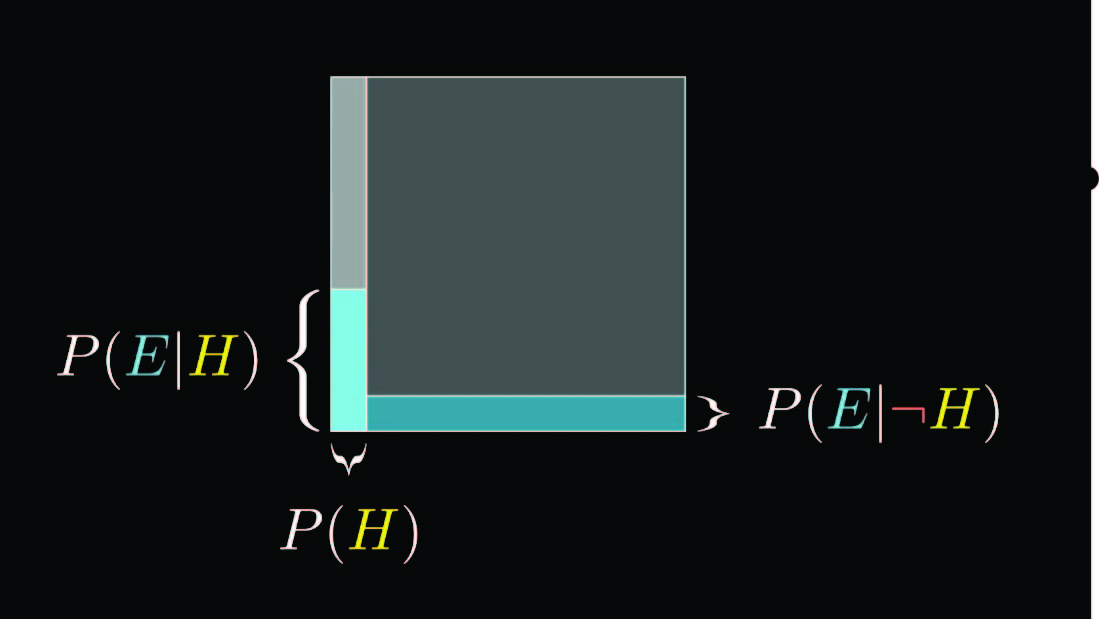

The box below (lifted from the 3blue1brown video on bayes’ theorem) represents $\mathcal{U}$. The entire box has probability $1$ (think about it as area). $E$ and $H$ are both collections of universes (somewhat confusingly, because I didn’t bother to change from 3b1b notation to my own, ‘E’ stands for ‘evidence’ in this box rather than being used for ‘event’, and ‘H’ stands for ‘hypothesis’).

$P(E \mid H)$ means: zoom into the part of the box corresponding to $H$, the bright-gray column on the left, and look at what proportion of that $E$ (the bright blue column) takes up. Mapping everything I built up above into this box visualization: A particular universe $\mathbf{U}$ is a singleton point on the box. Some event $E$ is an area in the box. The event space $\mathcal{E}$ is the set of all areas of the box (think an infinite number of bounding-boxes or weird shapes). Conditioning on an event means zooming into that part of the box and making it your entire universe. $R$ is some very small area in this box, and in practice we pretty much always want to be conditioning on the low-entropy manifold that $R$ lives on (think about a wavey sliver of the box - shapes we condition on don’t have to be rectangles).

Let’s say I’m publishing a paper and I have some data $D$ (“D” is shorthand for “the set of universes $E_D = {\mathbf{U}_i}$ in which the data was measured”). I want to figure out if some hypothesis $H$ that I have is true (a “hypothesis” is a set of universes $E_H = {\mathbf{U}_j}$ in which a guess I have about the universe is true).

Well, we can think about this: if I take all possible disjoint hypotheses, then they cover the entire sample space, $\bigcup_{i} H_i = \mathcal{U}$, and some subset of them has to overlap with $D$, e.g., be true: $D = D \bigcap \mathcal{U} = D \bigcap (\bigcup_{i} H_i)$ (this is the same as the law of total probability; we’re just not applying the probability measure after the set operations).

The human brain can’t literally figure out all possible hypotheses that fit observations that we see, so we do a brainstorming session to take the top $k$: ${H: P(D \mid \bigcup_{H_i}) > t}$, and we want the threshold $t$ to be as high as possible given the time we’ve given ourselves to come up with hypotheses.

Zoom into one hypothesis with high probability $H = \argmax_{i} P(D \mid H_i)$. Remember that this is an event: a set of possible universes in which our hypothesis was true. What we’re really doing here is trying to find the $H$ that maximally overlaps with $D$, e.g., maximizing some notion of the volume of $(H \cap D)/(H \cup D)$ by varying $H$ (after defining what we mean by ‘volume’). Finding the hypothesis that maximizes this intersection-over-union is the same thing as finding $\max_{i} P(H_i \mid D)$ (the best $H_i$ we’ve found so far is what we call a ‘theory’ in physics). This is (related to) what yudkowsky means when he says “a map that corresponds to the territory”.

Improving Scientific Thinking

Now that we have a somewhat reasonable formalization, let’s use it to make observations that make our scientific thinking more clear and give us action items when it comes to things like experimental design.

What does it mean to collect more data?

Collecting more data means that we now condition on $\hat{D} = \bigcap_i D_i$ instead. This is a smaller-volume subset of universes, and consequently there aren’t as many compatible hypotheses (e.g., it’s harder to overlap in our intersection-over-union). This is a good thing: it means that it’s easier to pick hypotheses during our brainstorming sessions that might ‘match’, because we’ve narrowed down the search space.

What type of data should we collect?

It seems to me like we would want to collect data that maximally reduces the volume of $\hat{D}$ (we really should define what we mean by ‘volume’ - I guess this is just the Lebesgue measure?). That way we’re maximally restricting the set of hypotheses compatible with that data (e.g., the ones with high intersection-over-union). The best way to do this is to find a hypotheses as disjoint with what we’ve already conditioned on as possible with as large a volume as possible, and then eliminate or not-disprove it by performing an experiment that could result in collecting data incompatible with the hypotheses.

What does it mean to eliminate a hypothesis?

We’ve conditioned on our data, so (in the basis of our data rather than the basis of $\mathcal{U}$ or $\mathcal{R}$), we have $P(D) = 1$. So if we had access to a full set of hypothesis that together fully overlaped the volume of our data, then we’d have $\sum_i P(H_i \mid D) = 1$. If we eliminate a hypothesis $H_j$ by collecting new data $\hat{D}$, then in the basis of that new data, $\sum_{i \neq j} P(H_i \mid \hat{D}) = 1$. Our other hypotheses weren’t eliminated; so the amount of probability that $H_j$ was responsible for must be dispersed into the other hypotheses.

(I’ll actually make the observation now that we should be taking integrals rather than summing, and doing everything on a continuous space as defined before, but I don’t feel like going back and fixing this, so just note that this is true and make the appropriate changes in your mental model, it’s not that different)

How can we incorporate causality?

In the causality literature, $P(A \mid do(B))$ means: let $do(B) = E_{do(B)}$ be the set of universes in which we force $B$ to occur. In what proportion of these universes does $A$ also occur?

This is different from $P(A \mid B)$, because the set of universes in which we force $B$ is different from the set in which $B$ occurs naturally. For instance, suppose $B$ is the set of universes in which I carry an umbrella, and $A \mid B$ is the set of those in which it also rains. Normally, a very large proportion of the $ \mathbf{U} \in B$ are universes in which I also expect rain. However, $do(B)$ zooms in on a very particular subset of $B$, in which I have the umbrella because I was just given it by force rather than because I expect rain. My expectation of rain is the true reason that $P(A \mid B)$ was high; removing the universes with this expectation makes the actual rain probability plummet. (We can map ‘expectation of rain’ in as well by defining it as a set of universes $\{U_{Ra} \}$)

(This one, unfortunately, doesn’t really get at the essence of judea pearl causality, which is that the $do$-operator severs incoming nodes in the causal graph for whatever it operates on)

Closing Thoughts

It definitely feels like there should be some notion of turning everything into a vector space equipped with an inner product (our IoU metric or some derivative), and then ‘finding good hypotheses’ becomes a search to find the few hypotheses that have high inner products with our data. I’d have to think about exactly how that translation would work. This might be a useful thing to think through later. I suppose orthogonal vectors in this case would correspond to fully disjoint events?

Leave a Comment